The following is adapted from a sermon that Aisha gave in CLF online worship on Nov. 6, 2022.

A few years ago, I was having a conversation with a friend about learning to love myself fully, especially my body. I was jokingly explaining that I never learned to dress myself in a way that was truly flattering to my body type. She explained that the problem wasn’t that I didn’t know, it was that I was conditioned through marketing to think fashion looked a certain way and only on certain bodies. Primarily what looks good on thin, white women — and those things simply didn’t look good on me.

She suggested I follow plus sized, Black women on social media. She sent me invitations to gorgeous Black models and activists who I continue to follow.

As their posts showed up in my feed, I was able to expand my notion of what is beautiful and as time went on, I was able to see myself through a more expansive and generous lens.

These fashionistas are unapologetic, fierce and simply beautiful.

One of the people I found myself in awe of was Leah Vernon, a Black Woman whose posts continue to expand my imagination with regards to fashion, because she does not exist in a prescribed paradigm. She is the author of a new book, Unashamed: Musings of a Fat, Black Muslim.

Through Leah’s posts and those of Black leaders like, Sonia Renee Taylor, Ijeoma Oluo, Jessamyn Stanely and adrienne maree brown, among others, I was able to change my perception of beauty through changing the default of what I was exposed to throughout my entire life.

Through a friend’s recommendation, I was able to challenge assumptions I held about myself and about beauty for my entire life. This has helped me experience beauty differently and in a much more liberated and loving way, for myself and others.

This brings me to an email the CLF received a while back about the assumptions the writer seemed to hold. The person, who is not incarcerated, wrote to us asking why they seemed to be getting the “prison ministry version of Quest.” They said that, though they support work with incarcerated people, it is not their work, and they have no interest in being a part of that ministry — they would simply like to get the traditional version of Quest.

Over two long email responses, I told this CLF member that as we center liberation at the CLF, we care about giving opportunities for all to grow an awareness that extends beyond an intellectual understanding that there are “people in prison.” For those of us who are not experiencing incarceration, reading the thoughts and feelings of those who are is powerful. I invited this member to consider the possibility that they have something to learn and be moved by something written by someone whose words you may not otherwise be exposed to, and emphasized that the Worthy Now Prison Ministry is not separate from the ministry of the CLF. We are one entity and one congregation that centers Unitarian Universalist values of community care.

This exchange and the response of this person to the changes in Quest, a publication that for decades centered primarily on the words of ordained clergy, had me thinking about assumptions being made about others.

We are a faith community that does not promise heaven or hell. In essence, we are trying to figure it out. Why are we here? What does it all mean? How do we navigate this beautiful, scary, joyful and painful thing we call life?

I don’t have answers to these questions and the hard truth is no one really does with any degree of accuracy. No one is an expert at being human, not even faith leaders.

What we can offer as faith leaders is a place to grapple with the questions and create a container that invites into an expansive and loving way of being.

Faith leaders receive training to become either ordained, credentialed, or lay leaders in order to have a shared understanding of the container we are creating. Faith leadership is not a science, it is where those given the sacred charge of ministry (in all its forms) choose to be in an accountable relationship with the members of the congregation and in many ways an accountable relationship to UUism itself. I center UU values in how I approach my faith leadership, a leadership rooted in religious education.

Revelation is not sealed, and as part of the search for truth and meaning, learning from those most impacted by oppression is a crucial way to learn the ways we need to do better and love more as we work to dismantle systems that actively cause harm.

When the three of us, the current Lead Ministry Team, started our leadership of the CLF, one of the aspects of this ministry we knew we wanted to transform was that of Quest and how this publication can more faithfully serve all of our members, both incarcerated and free world. The three of us were in agreement that Quest can both include reflections and sermons from faith leaders and our members, both incarcerated and those that are “free.”

In the email I referenced earlier, this CLF member took exception to being called a “free world member.” In retrospect, I realize that this person is accidentally correct to take exception to this term.

As Fannie Lou Hammer said, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

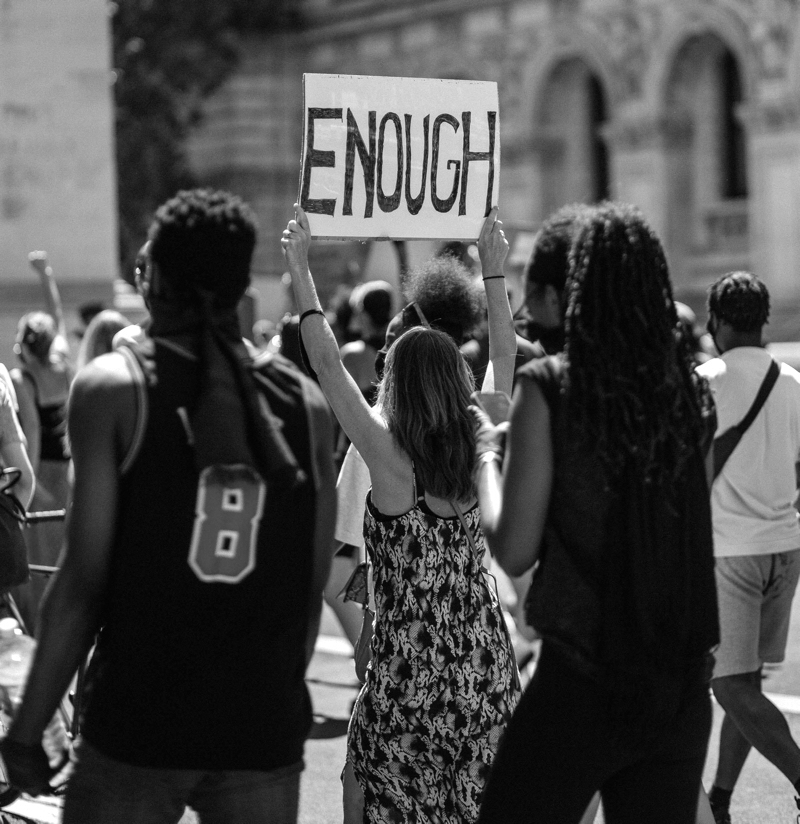

Every day in the U.S., it is painfully clear how those in power who want to affirm white supremacy and patriarchy are doing all they can to make sure no one is truly free. The rights of half the population have been taken away with the overturning of Roe vs. Wade. There are hundreds of anti-trans bills across the United States and there are people running for office in the U.S. that are running on platforms of intentional disenfranchisement of those with target identities. While the CLF is based in the U.S, the results of policies enacted by the U.S. government impact people all over the world.

It is more important than ever that those of us in faith leadership positions center the voices of those most cruelly impacted by the systems of oppression that harm us all.

However, those with privileged identities have been deceived into believing they are separate and somehow protected from oppression. This is a lie. Humans are inextricably connected and the destinies of the most powerful are tied to the most marginalized, history has demonstrated this over and over.

Countries with wealth disparities like the ones we have now in the United States do not last, and in fact topple.

We have an opportunity to save ourselves by caring for each other and learning from each other by being open to the reflections from those who are most in harm’s way. Not only Black people, but also indigenous people, trans people, immigrants, those with seen and unseen disabilities, but also learning from people who are incarcerated, most holding some or all of the identities I just listed.

Let us embrace the opportunity to be nourished and impacted by the reflections of people we may never meet in person, but whose lives matter.

I want to share with you the words of Joseph, an incarcerated UU and CLF member. Joseph shared their reflection of the idea of sacrifice. They write:

The value of sacrifice is relative. Without sacrifice, I would not be here living life as I know it. If my mother hadn’t sacrificed her time and put her dreams on hold, then she wouldn’t have been able to raise me so lovingly. She was 20 years old, barely an adult and I feel certain I wasn’t planned. She probably had many other plans. Maybe traveling, concentrating on school. I thank mom for her sacrifice, it was very valuable to me.

Some sacrifices seem small to us but can be very valuable to the recipient. Perhaps you sacrifice some time once a week to go visit a nursing home. If you have spare time, you would normally watch TV or spend it on the internet, you could make a sacrifice that is of little value to you, but could be of enormous value to the nursing home resident who has no family.

Our sacrifices are offering to the group soul of humanity. No matter how small or large, if it does good for one, it is good for all. Depending on my commitment and intention, my sacrifice doesn’t have to be public. When things are done without my attachment to the result, they are more pure and powerful. Some sacrifice all their lives, in order that others may live. Some make small sacrifices of that social awkwardness to overcome that to share a kind word with a stranger. No matter how small a good thing is, it is still good.

In sharing their reflections in Quest, incarcerated CLF members — people who have had their freedom taken away — are now giving the gift of their presence and reflections.

It is incumbent upon those of us with more privilege to examine our assumptions and do what we can to learn from those most impacted by this cruel and harmful system we call the United States. It is incumbent upon us to center love, community, compassion and liberation.

May we be humble in how we receive and move through this faith community and the world.