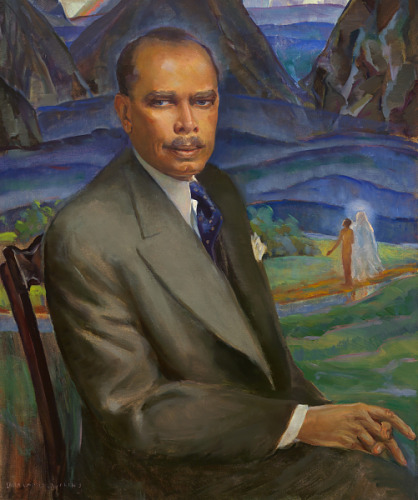

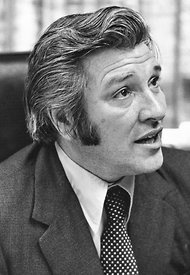

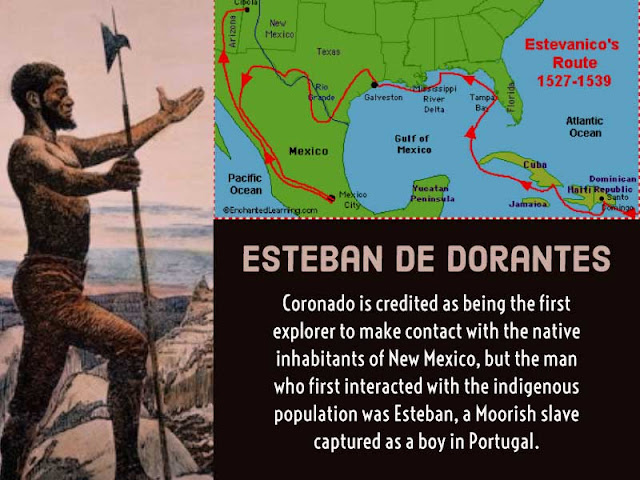

Tim's Senior high school photo doubled as an 8x10 glossy to promote himself as a teenage party DJ.

The other day it was siblings day on Facebook and I shared old photos of my Twin Brother Timothy who died on Valentine’s Day in 2004, 17 years ago now. We had a complicated relationship.

His short obit in the Chicago Tribune read:

Timothy Peter Murfin, 54, formerly of Chicago, IL and Portland, OR, died in Cincinnati, OH on Feb. 14. Born in Twin Bridges, MT on March 17, 1949 to Willard M. Murfin and Ruby Irene, nee Mills, Murfin, who have both preceded him in death. Survived by children Ira Samuel Murfin of Chicago and Shani Colleen Menz-Murfin of New York City; brother Patrick Murfin (Kathy) of Crystal Lake, IL; stepmother Rae Murfin of Alberton, MT; former spouse Arlene (Packer) Brennan (Michael) of Chicago; former longtime companions Luanne Menz of Georgia and Normandie Nunez of Portland, OR; and three nieces. Memorial service is pending in Chicago.

I was working alone at Briargate Schoolin Cary, Illinois where I was head building custodian. It was a Saturday, but a basketball program used the gymfrom 8 am to 9 pm. I had to be there and was little resentful of not spending Valentine’s Day with my wife. I was shampooing hall carpetswhich were encrusted by tracked mudand salt from a winter’s worth of boots. About 7 pm I got a call on my cell phone, a new-to-me gizmo that seldom went off. It was from Kathy with the news that my brother was dead.

It was a shock, but oddly not totally unexpected in that he had abused his body with alcohol and a virtual pharmacopeia of self-prescribed medication for many years. I was stunned, but went through the motions until the last kid and the last chatty parent was finally locked out of the building.

Two or three days later I was in a cardriven by Ira S. Murfin, Peter’s—he preferred to be called Peter, the Biblical name he had adopted upon entering a religious order years before—son. My middle daughter Heather Larsen was with us. We were driving through the night to Cincinnati to make final arrangements and collect whatever was in his “estate”—the few personal belongings he had hauled with him to Ohio after his virtual exile from Oregon. An odd conversation we had in that car—maybe more of a rambling monologue by me, would become the gist of the opening words of a memorial poem. More about that later.

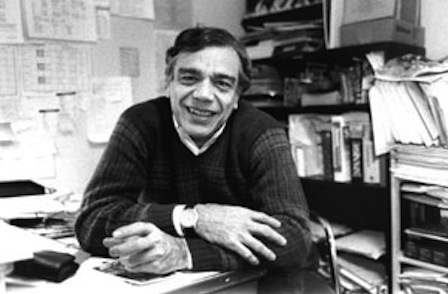

At our baptism at a Methodist Church in Montana in 1949. Mom Ruby has Tim, Dad W.M Murfin has me. Tim's font bath took. Mine evidently did not.

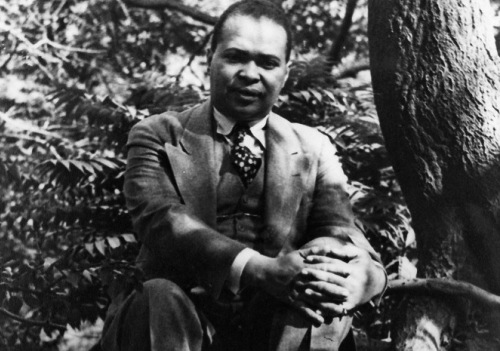

The two of us were adopted at birth by W.M. and Ruby Irene Murfin. Despite being twins, we were not identical. In fact in many ways we could not have been more different. Tim was dark haired and so good looking as a child that women stopped my mother on the street to compliment her. I was larger, blond, and from the beginning oafish. In school I was simultaneously a loud know-it-all showing off all of the hours of reading I did while still managing to fail at math and spelling. I had no friends and was a magnet for bullies.

Tim was not a star student or an athlete. None-the-less exuded a kind of charisma. Other kids swirled around him, naturally following his interests. From always being Roy Rogers in the neighborhood cowboy games, to being the 12-year-old leader of Cheyenne’s sidewalk surfers, to being the first guy in town with a Beatle haircutand Nehru jacket he was popular and naturally had the prettiest girlfriends.

In Cheyenne for Frontier Days. Tim, left, was always Roy Rogers and the hero, I was Hopalong Cassidy, cousin Linda, far right, was was Belle Star when she visited us.

When we moved to Skokie and Niles West High School he and his willowy girlfriend were elected to Prom court. He planned to be a radio disc jockey and got himself gigs hosting sock hops and basement parties with his portable record player and boxes of 45s.

I was into newspaper, theater, and increasingly radical politics. Tim got interested in religion and was soon a leader in Young Life, a denizen of church basement coffee houses, and talking about becoming a minister. Always, a gaggle of kids followed him.

I went away to college at Shimer. Tim stayed home, mostly to keep his adoring posse together. He attended Kendal College, a two year school in Evanston. I came home a long haired, dope smoking hippy and draft dodger. It turns out he had discovered marijuana too and the use of hallucinogens as spiritual practice.

After I left Shimer and moved to Chicago, I lived with him a couple of times. Each time he had a full house of roommates and acolytes. I was the improvident brother he found space for in an unheated room off of an Old Town kitchen or the unfinished basement of a Rogers Park townhouse. By then he had grown a patriarchal beard and seemed to be gathering his own hippy cult, which would literally gather at his feet as he smoked a fat one and waxed beatifically on arcane mysteries.

Tim married Arlene, a very nice young woman who worshiped him. She followedhim into an outfit called the Holy Order of Mans, which practiced some sort of mystical catholicism with a small c. He took the name Peter—the Rock of the Church. Together they were sent on mission to California. A few years late Arlene returned to Chicago with their toddler son Ira.

Peter drifted out of the Order and pursued various spiritual paths with complete earnestness. He lived in Portland and had a day job at an early big box hardware store. But he yearned to be a saint. He found folks who thought he might be. Got into another relationship, had a daughter, Shani and lost that family to boutsof depression and heavy drinking and self-medication.

He cleaned himself up in AA and characteristically became a star. Soon he was speaking all over Oregon and northern California and re-inventinghimself as a spiritually based addiction councilor. He was making big plans and chasing various gurusand guides looking more for tips on how to become one of them than for enlightenment. Or so it seemed to me from my great distance in Chicago when he would phone with plans.

Eventually he became a substance abuse specialistwith the county department of probation. He entered another relationship with an adoring older woman with a teen age daughter. But the depression never went away and he fell off the wagon in secret repeatedly. Each episodebecame more intense. It became harder to hide.

In all of those years I saw Peter only three times. We came to Missouri where he was asked as an ordained priest by my fatherto conduct my mother’s funeral. He did so with grace, although his relationship with my father was strained. It would become an obsession which he would pour out to me in drunken middle-of-the-night telephone calls.

My brother, then known as Peter visited Chicago from Portland in 1983 shortly after the birth of my daughter Maureen. This was taken on an evening outing to Buckingham Fountain. Peter was in front with our oldest daughter Carolynne and the baby. My niece Laurie is leaning on him. His son Ira and ex-wife Arlene Brennan and Kathy and me in the back row. Middle daughter Heather must have snapped the picture.

In the summer of 1983 just after Kathy and my daughter Maureen was born, Peter stayed with us for a week. It was also his first visit with his ex-wife and son. He showed up trim, tanned, and handsome. His black beard was neatly trimmed, his hair barberedto a fare-thee-well, his clothes West Coast casual sharp. I was still a scraggly post-hippy in thrift shop clothes and a cowboy hat. I had the family reputation, well earned, as a heavy drinker. I did nothing to hide it. Peter was supposedly sober. But Kathy walked in on him pulling from the fifth of whiskey he had hidden in is bag. It turned out he was killing a bottle a day or more but never actually seemed drunk.

The last time I saw him alive was after we had moved to Crystal Lake. He was back for another visit to Ira and spent most of his time in Chicago, but came up for a couple of days with us. By this time he was in rougher shape. He ambled over to St. Thomas Church across the street where Kathy was an active parishioner and RE volunteer, to ask the Priest for permission to say a private mass at their altar. He explained that he was also “an ordained Priest in the Higher Order of Melchizedek” and required to say mass daily. He was upset that he was turned down, saying that some priest pal in Portland had let him use his church. He made Kathy and the girls uncomfortable.

Back in Portland his life slowly unraveled. The relapses became more frequent, the depression blacker. He wrecked cars, lost his job. Normandie stood by him as long as she could, and supportedhim in the later years. But in the end he wrecked that, too. He exiledhimself to a closet of a room in Eugene where some former acolytes tried to help him. He burned through that, too.

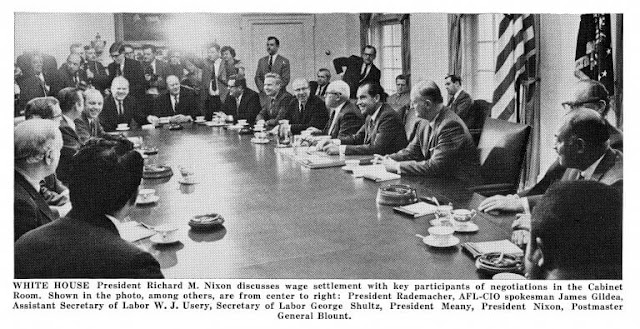

He was virtually homeless and on the run from the law for failure to pay fines for his traffic accidents. David Sellers, an old friend who he had met hangingout at WLS radio studios while he was in high school and who had lived with us in that Old Town apartment, offered him a bed in suburban Cincinnati. He was reportedly trying to get himself together and was apparently sober. He had settled into regular Catholic worship, but he still received tons of mail from all of the cults and gurus he had associated himself with. Although he couldn’t find work, he finally got qualified for Social Security Disability. Just after accomplishing that he came home one day, sat down on his bed and died of a massive heart attack.

To our amazement, drugs were not directly involved, except that long abuse had generally wrecked his health.

Ira, Heather, and I arranged to have him crematedand gathered the boxes of his life timewhich were crammed in the closet and under the bed of his room. Tons of mystical books, art work, beads, crystals, candles, vestments, journals in his meticulous calligraphy. We packed the urn and the stuff and returned to Chicago. The stuff mostly went into storage, Ira and I each keeping a few items.

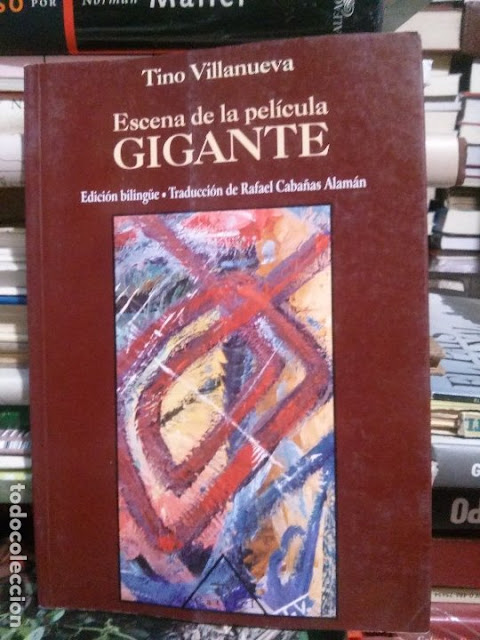

We arranged for a Catholic funeral massat an old Polish parish just west of the Loop. The Mass was said by, a Milwaukee priest and the brotherof Arlene’s second husband Michael Brennan. It was solemn and holy and in a lovely old chapel. Peter would have approved. After the Mass folks got up to testify about him in one way or another. When my turn came I read a suite of six elegies that I had been working on for weeks. This is what I read:

Elegies for My Brother

Timothy Peter Murfin

March 17, 1949-February 14, 2004

I.

Hurtling down an Interstate on any black night,

say the route angling south southeast from Gary

for Indianapolis then slung around the racetrack

to Cincinnati, Queen City of the West,

you realize in an instant that this great gray marvel

was not constructed for the likes of us,

mere civilians on inconsequential errands

encapsulated in puny steel,

that it was wrought for Commerce,

for that endless caravan of behemoths

jeweled in red and yellow charging indefatigably

for endless rendezvous with profit,

and that our vagrant desires to come home or to escape,

to begin a new life or repeat by rote an established tedium,

to make love or to break tender hearts,

or on this one night in this one box loose amid that stream,

to unite the living with the dead,

seize an unworthy opportunity to tag along for the ride.

II.

Roy Rogers is dead.

The King of the Cowboys with his nickel plated, pearl handled revolvers

resplendent in pearl snap shirt and neckerchief

with a cockeyed and confident grin,

the hero of every summer morning adventure

with Dale Evans at his side

and Hopalong Cassidy on loan from the two reeler next door,

has fallen from Trigger,

Bullet noses his lifeless sprawl in the dust.

[Here sing Happy Trails to You]

Happy trails to you, until we meet again.

Happy trails to you, keep smiling’ on ‘till then.

Who cares about the clouds when we’re together?

Just sing a song and bring the sunny weather.

Happy trails to you, till we meet again.

Happy trails to you, ‘till we meet again.

III.

Youth bestows its virtues capriciously,

a dollop of beauty here, audacious valor there,

sweet innocence and brash confidence

doled out as if rationed by a miser,

many seeming to be passed over

and left with only churlish resentment,

bad skin and worse judgment.

But he stood beneath the fountain,

let its waters bathe him in every gift

a dark handsomeness,

a dj’s soothing voice,

charm,

charisma,

so that he dazzled his way through life,

gathering around him tight circles

not just of friends, but followers

who dreamed his dreams.

The hippy guru of Sheridan Road,

they gathered as acolytes at his feet

as he sat with Old Testament patriarchal beard,

eyes blazing one moment,

the beatific smile of yoga saint the next,

in hallucinogenic communion.

And I, no account wastrel with dim prospects,

swung on the icy path of an asteroid

orbiting far, far from that blazing Sol.

IV.

One year, just before Christmas,

he wrote from somewhere on the West Coast.

This year, could I send him a blank book,

bound in leather, hand stitched,

virgin velum pages waiting for his pen?

I want, he wrote, to be a Saint

and no mere tablet or collegiate spiral notebook

would be worthy of the great and inspirational words

which he would meticulously enter

in that fine calligraphic print he assumed.

It struck me, even in my heathen ignorance,

that saints had no ambition but simply were.

But I hunted through the stationers until I found the perfect journal,

inscribing on its fly leaf my own haughty judgment—

See Ecclesiastes, Chapter 1, Verse 2

Vanity of vanities saith the Preacher,

All is vanity.

V.

He took his religion like he took the whiskey

that he stashed,

straight from the bottle,

no ice, no diluting soda.

He demanded the real thing,

raw and powerful,

burning the throat on the way down

but leaving a warm belly glow.

He may have wandered here and there

amid crystals and pyramids,

astrologers and New Age frou-frou,

but settled only where the mysteries

were deep and hard.

For him no dallying among the ladies of

Saturday morning yoga and meditation,

no time for the plain/simple Buddhism

of the agnostic heart so embraced by

disappointed Western rationalists,

but the stern, demanding Tibetan school

with spinning prayer wheels,

real gods and real demons,

The Book of the Dead.

And no Vatican II Catholicism for him,

no priests in sweaters named Father Phil,

no guitar masses and suburban congregations in Ban Lon,

no cheap and easy grace,

only the penitent's worn out knees,

the endless rosaries endlessly repeated,

icons,

medals,

Holy Water,

the prophetic apparitions of Mary,

the stigmata of Padre Pio

in which, if he could,

he would dip his handkerchief

to press to his lips to kiss.

VI.

Something inside of him was broken.

He knew it and spent a questing life

trying to find it,

trying to fix it.

Was it some trauma of childhood,

inflicted by the fragile, damaged woman who raised us

or the god-like but distant father?

He often thought so, obsessed over each moment

of remembered agony and rejection,

taking the hard knocks of ordinary childhood

and building an edifice of unremitting pain,

unable to forget what he had constructed,

unable to forgive.

Or, now that Freud has been cast aside as Fraud,

was it just some accident of biochemistry,

a roll of the dice that elected him

by alchemy of genetic chance

to have neurons that misfire just so?

As a former Friend of Bill W

did he have to assume responsibility

and seize control of the disease himself,

or did the pickling years of hidden bottles,

the various stews of pharmaceuticals prescribed

and self-prescribed

finally overcome that mind?

Was it all three?

Does it matter?

He was broken and tried to repair himself as best he could

and in the process leaned how to balm the wounds

of other troubled souls,

but like the Physician, could not heal himself.

—Patrick Murfin