The George Floyd story is really three separate stories: how he died, how he fits into the larger story of police brutality against black people, and the demonstrations and riots that have happened around the country since his killing.

His death. The first story is the most difficult to watch, but the easiest to tell: Last Monday in Minneapolis, police officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd by kneeling on his neck “for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, with 2 minutes and 53 seconds of that occurring after Floyd was unresponsive”.

We know the timing that exactly because a bystander uploaded a video to Facebook. It shows Floyd repeatedly complaining that he can’t breathe, and then becoming motionless while bystanders plead with police to “check his pulse” and ask the policeman who was keeping the growing crowd away “You going to let him kill that man in front of you?”. Chauvin doesn’t get off Floyd’s neck until an ambulance has arrived and a stretcher is ready to receive his (possibly already lifeless) body.

The police account, from a few hours before the video went viral, tells none of that. The New York Times summarizes:

Minneapolis police said they were investigating an accusation of forgery on Monday night in the southern part of the city. They confronted a man who was sitting on the top of a blue car. The police said the suspect had “physically resisted officers” as he was placed in handcuffs. He appeared to be “suffering medical distress,” according to the police statement released on Monday night after an ambulance was called to the scene.

That account is true, as far as it goes. Floyd was being arrested on a complaint that he had tried to pass a counterfeit $20 bill at a local grocery. NBC reconstructed the arrest from a number of video sources. At times Floyd struggled with the police arresting him, but he presented no weapons and was always greatly outnumbered. (According to the criminal complaint against Chauvin, the struggle you can barely make out in the NBC video is Floyd resisting being put in the squad car.) At no point did he seem to be getting away. When Chauvin put his knee on Floyd’s neck, Floyd was already handcuffed.

Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey commented:

The technique that was used is not permitted; is not a technique that our officers get trained in on. And our chief has been very clear on that piece. There is no reason to apply that kind of pressure with a knee to someone’s neck.

The four police officers involved in the incident were fired on Tuesday. On Friday, Chauvin was arrested and charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. [1] According to the local Star Tribune, he is the first white police officer in Minnesota to be charged in the death of a black civilian.

The other officers have not been charged with anything, but the county attorney says they are under investigation and charges are expected. Local Channel 9 speculated on what those charges might be:

The most serious charge the other three fired officers could face is aiding and abetting the murder. “That could be giving him a tool or weapon, it could be keeping people away from interfering with that was going on,” Mark Osler, a former federal prosecutor, told FOX 9.

Friday, a Washington Post editorial expressed dissatisfaction with the official response:

Minneapolis’s own police have done little to suggest they can earn the trust of the community they are sworn to serve. They have not released body-cam footage of Mr. Floyd’s arrest, nor apologized for the specious statement they published about the incident, which elided the fact that Mr. Chauvin’s knee choked Mr. Floyd. The head of the city’s police union, Lt. Bob Kroll, said “now is not the time to rush to judgment” on Mr. Chauvin or the other officers at the scene, who did nothing to interfere as Mr. Floyd begged for his life.

Racism and American police. Excessive violence against black people accused of crimes is a very old story in America. By various accounts, thousands of blacks were lynched between the Civil War and the 1930s, often on little more than a false accusation. By definition, a lynching is an extra-judicial killing, but local law enforcement officers commonly either participated or looked the other way. (For example, the local sheriff was identified as a conspirator in the Mississippi Burning murders of three civil rights activists in 1964.) I don’t know any estimate of the number of African Americans who have died in police custody since the end of slavery. Such killings were easily attributed to the suspect resisting arrest, attempting to escape, or committing suicide in prison.

For most of my lifetime, whites have regarded police brutality against black people as a they-said/they-said story. Blacks almost universally complained that police treated them more harshly than whites, and statistics showed that blacks were arrested, charged, and convicted far more often. But police said that blacks committed more crimes and were more likely to have a bad attitude towards police. Most white people never saw police arresting or otherwise accosting blacks, so the problem was easy to deny, ignore, or minimize.

The advent of ubiquitous video has changed all that. In recent years, the whole world has seen police choke Eric Garner to death while arresting him for selling untaxed cigarettes, shoot 12-year-old Tamir Rice dead for playing with a toy gun, shoot Walter Scott in the back while he was running away from an officer who had stopped him for having a bad brake light, and many similar incidents.

Those videos made us see other incidents differently, even if the actual death was off-camera: John Crawford III was shot dead in a WalMart for carrying a toy gun he was thinking of buying. Stephon Clark was shot dead in his grandmother’s back yard when police mistook his cellphone for a gun. Philandro Castille was riding with his girl friend and her four-year-old daughter when a policeman stopped the car. Castille informed the officer that he had a legal gun in the car, and the officer shot him dead. Freddie Gray died from a “rough ride” that police gave him back to the station after arresting him for carrying a knife.

The great majority of these incidents — even the ones caught on video — resulted in no jail time for the police involved. No one was indicted for Garner, Rice, Crawford, or Clark’s deaths. The officer who killed Castille was acquitted. Gray’s death resulted in a mistrial, some acquittals, and dropped charges. Walter Scott’s killer was convicted on federal charges, eventually, after his trial on a state murder charge ended in a hung jury.

Police have also tended to look the other way when white civilians kill blacks. Trayvon Martin was shot dead by a neighborhood watchman as he returned to his father’s fiance’s house after buying Skittles at a convenience store. Rather than treating the shooting as a crime, police returned the shooter’s gun and sent him home. Massive protests pushed local authorities to indict the shooter eventually, but he was acquitted.

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the American justice system doesn’t regard the killing of a black person as a big deal. The anti-brutality movement is called Black Lives Matter in response to the apparent reality that they don’t. [2]

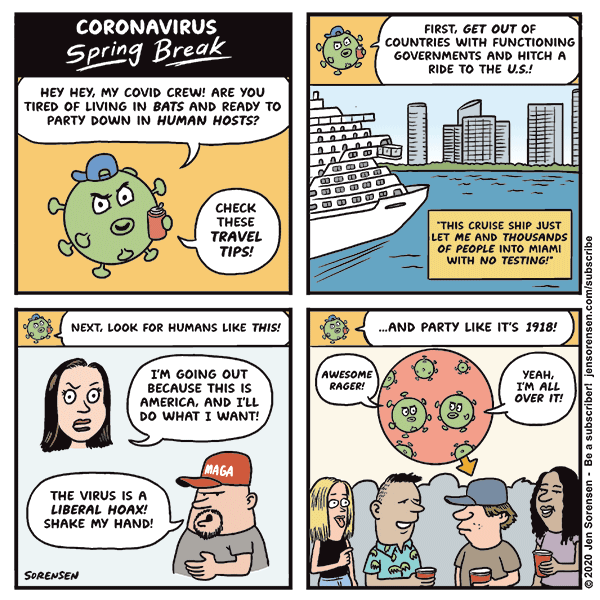

Recent events. By the time Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck, outrage had already been building for some while.

In late February, Ahmaud Arbery was killed in Brunswick, Georgia by two white men (a retired police detective and his son) while he was out jogging. The killers told police they suspected him in some local burglaries. For months the police took no action and the case got no attention in the press. But in early May, a video of the incident (which police seem to have known about all along) went viral. It showed Arbery being chased down and shot by three men in two trucks. It looked a lot more like a lynching that the resisting-citizen’s-arrest story the killers told.

Within two days of the video’s release, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation had gotten involved and arrested the two men in the lead truck. The third man, who videoed from the second truck, was arrested later.

How, the nation wondered, could police have sat on this video for months without making an arrest? If the video hadn’t leaked, would the killers have gotten away with it?

Another recent case generating outrage: Breonna Taylor, a Louisville EMT. Plain-clothes police with a no-knock warrant burst into her home (her boyfriend claims without identifying themselves as police), setting off a gun battle in which Taylor was killed and her boyfriend wounded. The warrant was to look for drugs, which they did not find. The boyfriend’s story — that he thought he was defending against a home invasion by armed criminals — seems pretty credible.

Echoes of Ferguson. Before we get into this week’s demonstrations and riots, I want to talk about the last time something like this happened.

In 2014, after the Michael Brown shooting in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, demonstrations erupted and sometimes turned violent. I commented at the time on the coverage from Fox News and other conservative media, which framed the community reaction as a great mystery: Most of these people never knew Michael Brown and had no idea whether the police were telling the truth or not about his killing. What riled them up so much that they had to go break windows or burn down a store?

If you came to the Ferguson story with that question in mind, racist stereotypes provided an obvious answer, which Fox didn’t need to spell out (though some right-wing voices did): The Brown shooting was just an excuse for young black men to indulge their inherently lawless nature.

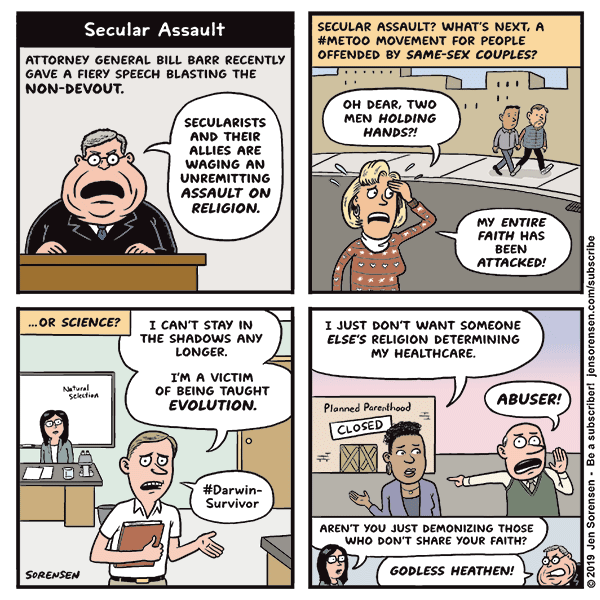

I addressed this “mystery” in “What Your Fox-Watching Uncle Doesn’t Get About Ferguson“, a piece that I think holds up pretty well after nearly six years. What Fox did wrong was present the Brown shooting as a one-off event, when the real story was the ongoing predatory behavior of the Ferguson police towards the black community. [3]

The right story begins not with Officer Wilson’s bullets, or even with Michael Brown in the convenience store, but with a community where lesser forms of police abuse are an everyday occurrence. … So it’s no mystery at all why people who never met Michael Brown have been out on the streets. Brown’s death is part of a bigger issue that they all have a stake in: How can the police be gotten under community control, and disciplined to treat the community with respect? …

What’s rare about the Brown shooting isn’t the shooting itself, but how visible everything is: The body was lying in the street for hours. The eyewitnesses have been on TV. Nothing in the autopsy or other available evidence contradicts their testimony. If the police don’t have to answer for this, then what are the limits? Is there anything they can’t sweep under the rug?

This week’s responses. That’s the context to keep in mind as you think about the sometimes-violent demonstrations that we’ve seen around the country since Floyd’s killing. It isn’t that thousands of people have suddenly decided to care about a guy they’d never heard of a week ago, and it’s not that lawless animals have been turned loose. The anger being expressed in these demonstrations, by both peaceful and violent demonstrators, is largely personal anger. George Floyd symbolizes that anger, but it’s much bigger than him.

Very large numbers of black people have had their own bad experiences with police, incidents where they felt humiliated or threatened or disrespected. (One young man in Ferguson schooled a condescending Fox News reporter: “We go through this shit every day.“) And for the most part they have had no recourse; no one who had the power to demand justice would take their complaint seriously.

So when they see the tape of Chauvin killing Floyd, their response isn’t, “Oh my God, can you believe that?” but “There! Look at that! That’s how they are!” Not “I can’t believe stuff like that happens in America” but “Finally somebody got the goods on them.” [4]

And at the same time, there’s the fear that even with this kind of evidence, nothing will change. Maybe Chauvin will be tried and maybe he’ll even be convicted, but maybe he’ll get off somehow, as so many others have. Maybe the other cops have been fired, but probably somebody — maybe even Minneapolis again — will hire them and put them back on the street. Or maybe they’ll be the rare cops to pay some kind of price for their racism, but the racist policing system as a whole will rumble on.

There is no reason for the demonstrators to have faith that something else will happen, that America finally gets it now. That’s why they’re on the street.

For comparison, think about school shootings. Again and again — Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland — an event is so shocking that it rises above the usual platitudes. And for a moment you think: “Now. Now something will change, because things like just can’t go on.”

But they do go on. Sometimes nothing happens, and sometimes there’s some incremental change in how we sell or track guns. But before too long there’s a new shooting, one even more horrible than the last one. And we go through it all again. Remember how that feels?

Riots. What we saw rising through the week and then reaching a crescendo over the weekend was a pattern of peaceful demonstrations by day and violence by night — not just in Minneapolis, but in cities across the country.

I don’t know how to cover the destruction, or even how to grasp it. A news network may show you a store being looted or a police station being burned, but are all the stores being looted? Is the whole city burning? The destruction seems widespread, but I don’t know how to get a handle on it.

I think it’s important, though, that riots not become the story. The original injustice — both specifically in the Floyd case and generally in the racial bias of our law enforcement — needs to be the story. Yes, the riots need to stop. Yes, people who use the cover of the chaos to commit crimes should be arrested and punished. And we need to take a hard look at crowd-control policing to see whether its tactics set off people who might otherwise disperse on their own. But just returning to the status quo is not a solution, because before long there will be another George Floyd, and then it will happen all over again.

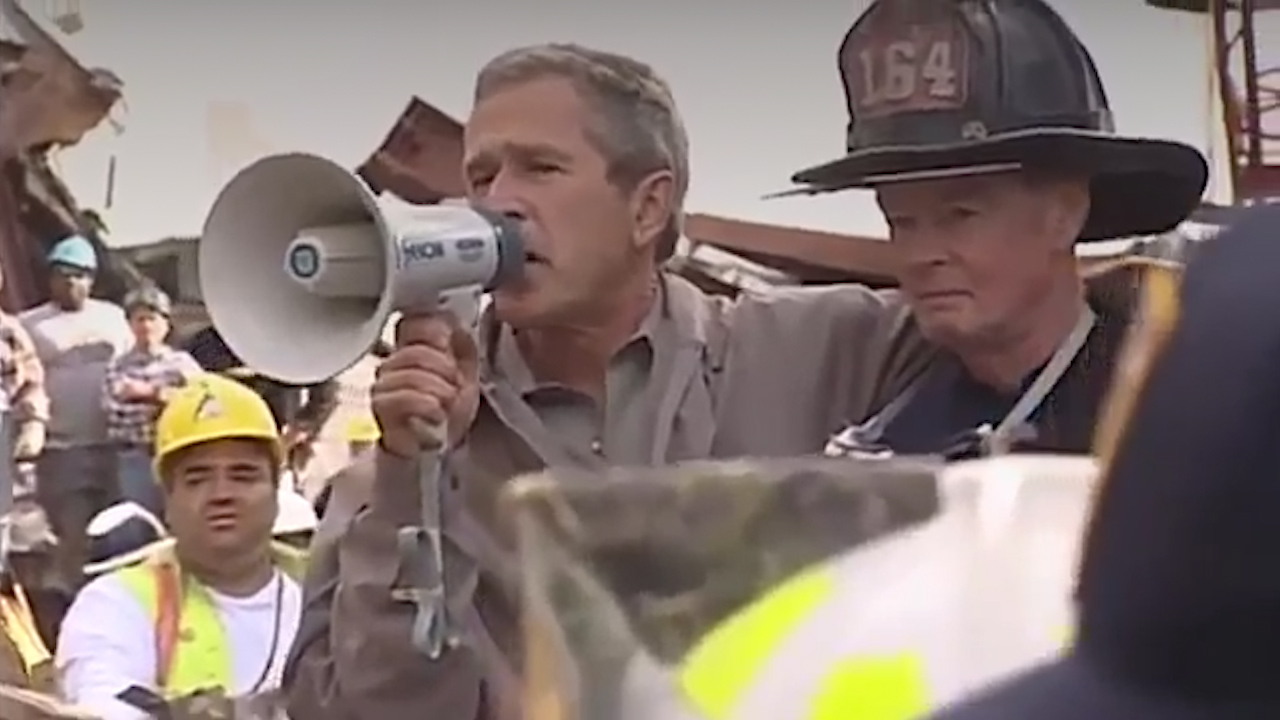

I think it’s important to remember that peaceful protest was tried and it failed. Remember Colin Kaepernick? What he was protesting when he knelt during the national anthem was precisely the racist nature of policing in America. The main result of Kaepernick’s protest was to end his NFL career, largely because Trump wouldn’t let up. LeBron James reminded us of this by posting this photo with the comment “This is why”

When you suppress peaceful protest against legitimate injustices, and punish the people who do it, you make violent protest inevitable.

And I don’t want to hear the platitude that violence never changes anything. In fact it does, and I think we’re seeing that now. The riots are sending white America the message that this can’t go on. It could have heard that message when Eric Garner said, “I can’t breathe.” It could have understood that message when football players knelt. But it refused. Now the message is being sent with fire and broken glass.

This can’t go on.

The agitators. Finally, there’s the mystery of the Umbrella Man, and an indeterminate number of others like him. A white man dressed in black, hiding his face behind a gas mask and an umbrella, got the Minneapolis riots started by calmly and methodically smashing the windows of an AutoZone with a hammer. He then walked away. He does not seem to be either a protester or a looter; he’s just there to catalyze the transition from protest to riot.

There are many similar stories of mysterious people, many of them white, who perform some initial act of violence and then vanish. Sometimes they arrive in trucks with no license plates.

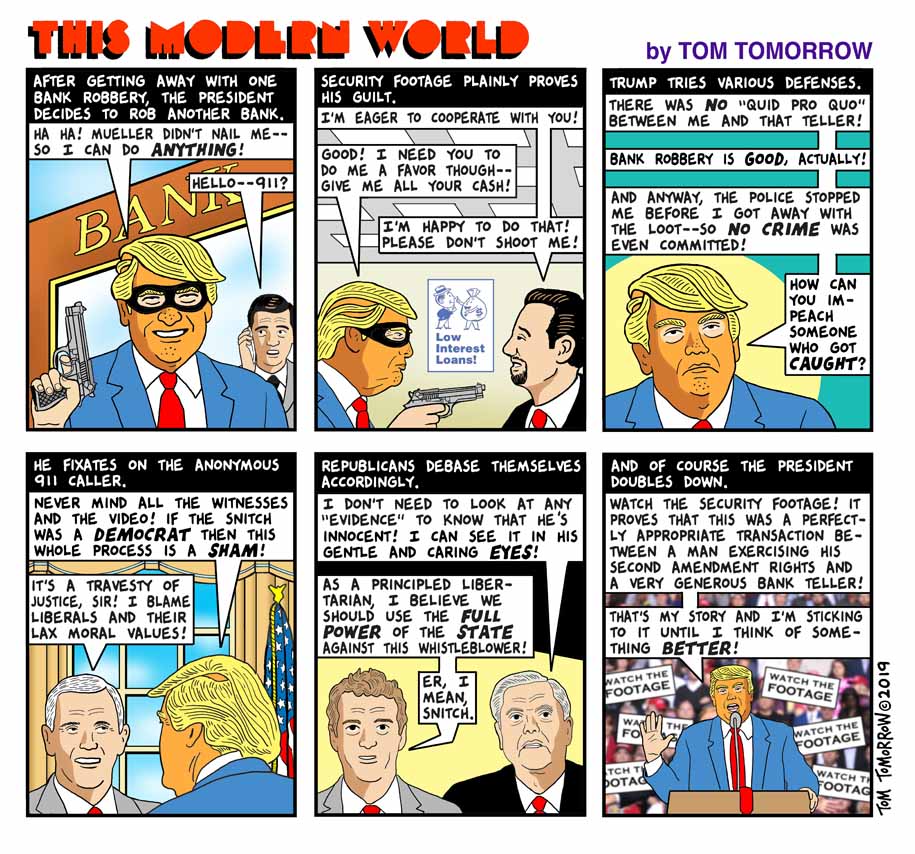

So far, a lot more is being said about these mystery men than anyone actually knows. Some say they’re white supremacists trying to set off the race war that their rhetoric says is coming. Trump says Antifa is behind it. [5] A number of protesters in Minneapolis suspect undercover police of agitating the violence to discredit the peaceful protests. (In the Umbrella Man video, bystanders keep asking “Are you a cop?”)

Any of those stories might have been false originally, and then become true. If you’re an isolated white supremacist or a left-wing anarchist, and you hear a false report that people like you are trying to turn the protests into riots, maybe you go out and do it without orders from anyone.

All those explanations need to weighed against the need of local officials to deny that their own constituents are so disillusioned that they’re ready to start burning stuff down. Blaming it all on “outsiders” is an easy out for them.

My advice: Pay attention to actual cases and the observations of specific witnesses, but don’t take anybody’s conclusions seriously yet.

[1] A local TV station summarizes what Chauvin was and wasn’t charged with.

A person commits third-degree murder when the person does not intend to kill another person but does so by acting recklessly, or “without regard for human life.”

It can lead to as many as 25 years in prison. The manslaughter charge carries a sentence up to 10 years, and is easier to prove.

A person commits second-degree manslaughter when their negligence causes another person’s death. Manslaughter only requires the person to create “an unreasonable risk,” while third-degree murder requires the person to act “without regard for human life.”

The more serious charge of second-degree murder would require establishing that Chauvin intended to kill Floyd, and first degree would mean that he planned the killing.

So it depends on what Derek Chauvin was thinking. If he walked into the situation thinking “I’m going to kill that guy”, it’s first degree. If in the moment he realizes “I’m killing this guy” and continues, that’s second degree. If he just thinks “Eh, if he dies he dies”, that’s third degree. If he should have known that Floyd’s life was at risk, it’s manslaughter even if he didn’t know.

In my personal opinion, the Floyd killing is second-degree murder. But if I wanted to give myself the best chance to win in court, I’d do what the prosecutor has done. I’m not sure I could prove to a jury that the thought “I’m killing this guy” went through Derek Chauvin mind (though being surrounded by people yelling “You’re killing him” should have given him a clue). Proving that Chauvin acted recklessly and should have known Floyd might die seems much easier.

[2] That’s why the response “all lives matter” is so off-base. If all lives really did matter, there would be no need to assert that black lives matter.

[3] That behavior was laid out in detail months later in a Justice Department report. One key quote:

Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs.

In other words, the police went into the community looking for things to fine people for, not to protect life or maintain order. The racial attitude of the police was characterized by things like this:

A November 2008 email stated that President Barack Obama would not be President for very long because “what black man holds a steady job for four years.”

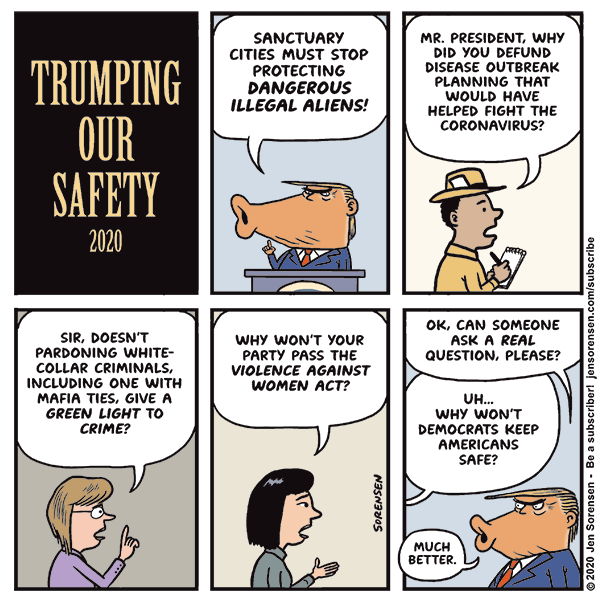

[4] The Trump administration is still in denial about this. Sunday on CNN, White House National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien rehashed the full a-few-bad-apples story.

No, I don’t think there’s systemic racism. I think 99.9% of our law enforcement officers are great Americans and many of them are African-American, Hispanic, Asian. They’re working in the toughest neighborhoods, they got the hardest jobs to do in this country. … There are some bad cops that are racist, there are cops that maybe don’t have the right training,. There are some that are just bad cops and they need to be rooted out because there’s a few bad apples that are giving law enforcement a terrible name.

What the administration sees is a PR problem, not a race problem. The thing to fix is not black people getting killed, but police getting “a terrible name”.

A lot of people on social media are sharing this Chris Rock quote:

Some jobs can’t have bad apples. Some jobs, everybody gotta be good. Like … pilots. Ya know, American Airlines can’t be like, “Most of our pilots like to land. We just got a few bad apples that like to crash into mountains. Please bear with us.”

[5] Over the years, Trump has said a lot of nonsense about Antifa, which is not even an actual organization so much as a collection of local groups who share some ideas and tactics. The general idea is that fascists are violent, so anti-fascists need to be prepared to match their violence. But Trump needs a left-wing group to distract from white supremacist violence, so Antifa is it.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-sltrib.s3.amazonaws.com/public/NL2T6XTQGRHRLGMS7HJTRSGH7Y.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/Y36AJWUQQYI6VEZCUKPHL374SM.jpg?imwidth=2048)

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-sltrib.s3.amazonaws.com/public/O5WD2VDIK5CKDG2Z2R6H7BA7UI.jpg)

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19935658/world_leader_ratings_1_high_low.jpg)

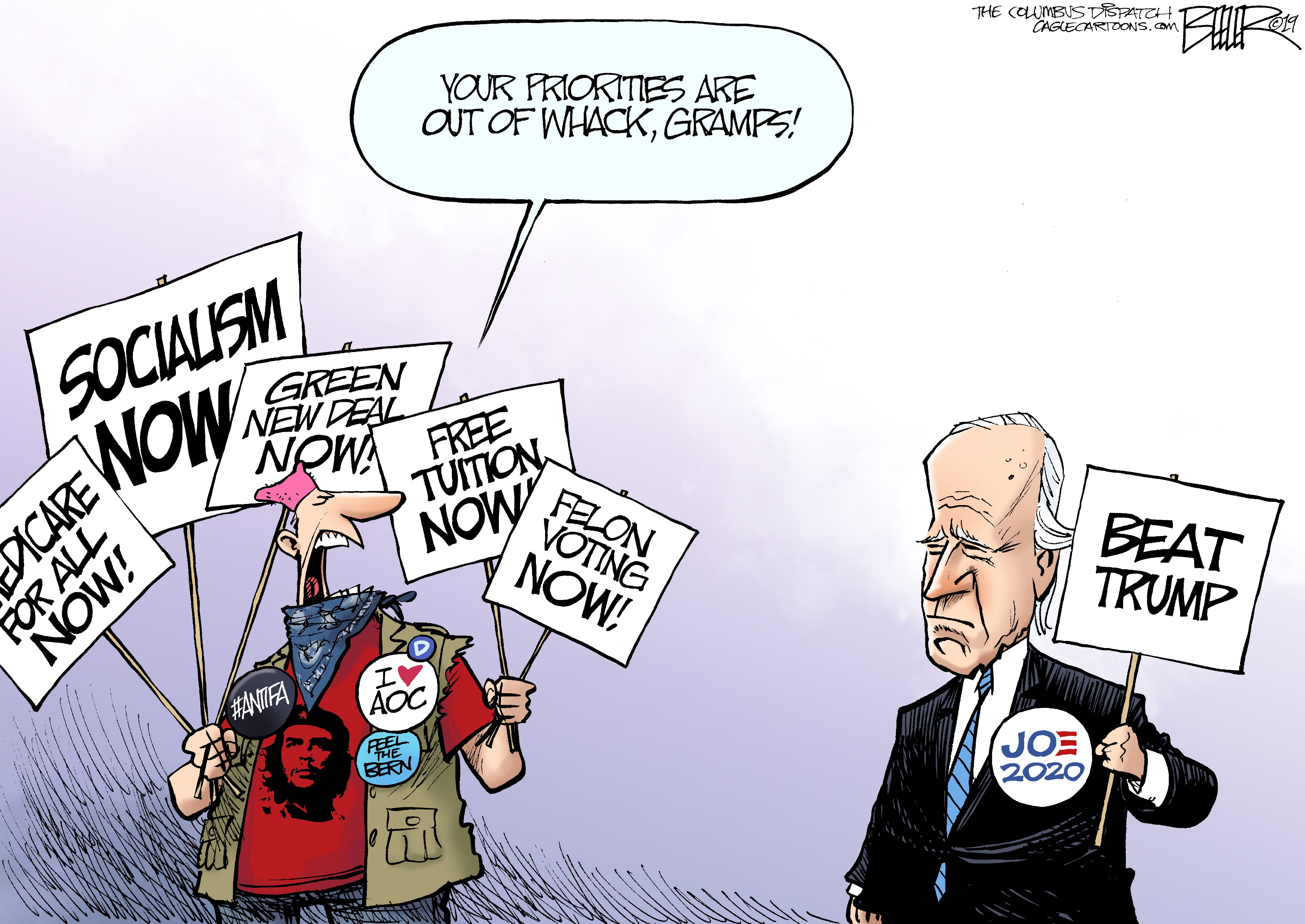

Super Tuesday is tomorrow, and I’m voting in the Massachusetts primary. I’m going to vote for Elizabeth Warren.

Super Tuesday is tomorrow, and I’m voting in the Massachusetts primary. I’m going to vote for Elizabeth Warren.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/editorial_cartoon/2020/01/07/theo-moudakis-lies-to-date/theo_moudakis_lies_to_date.jpg)

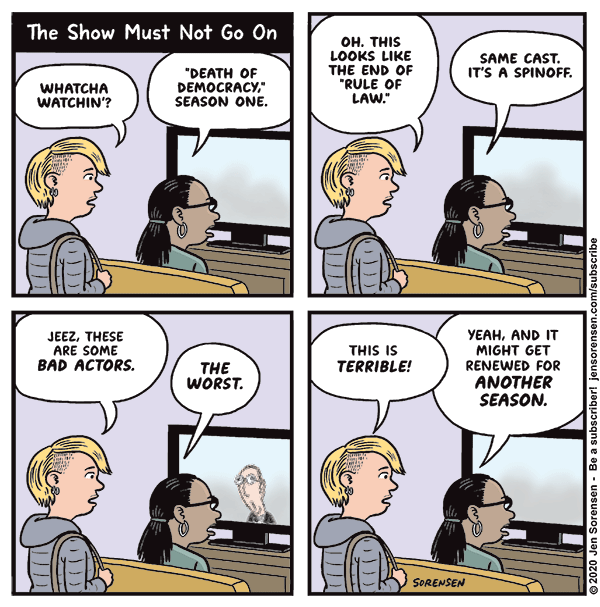

The Roger Stone trial started, which means that we might finally find out what all those redactions in the Mueller Report were about.

The Roger Stone trial started, which means that we might finally find out what all those redactions in the Mueller Report were about.  The anonymous Trump official who wrote a controversial op-ed a year ago

The anonymous Trump official who wrote a controversial op-ed a year ago

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15994811/1ee34cbd_634f_41e7_8654_fccbf479c940.jpg)